When you think of real-time reporting, you may well conjure up the image of a reporter on the street uploading photos and videos from their mobile. Speed and efficiency are king. Spare a thought then for Mitchell Zuckoff, the Shackleton of live reporting, who, armed with a BGAN, published his Rock Content event from one of the most remote places on earth.

Zuckoff is an author, reporter and journalism professor based in Boston. He has recently returned from Greenland where he accompanied the U.S. military and coastguard in their attempt to recover the bodies of servicemen who had been ‘entombed inside a glacier’ since World War II. Having already written a book about the lost men and the search for their location, he knew he had to join the mission to bring back the bodies.

Going to Koge Bay, Greenland was one thing, but for a professional storyteller, documenting the mission was key. Mitchell toyed with the idea of turning the trip into a new chapter for the paperback edition but, as a journalism professor who teaches his students about digital innovations, he thought he ought to practice what he preaches. “I should be experimenting with new forms and new media so I can talk about my own experiences,” he says. And so the idea of publishing the story on a real-time platform was born. He approached the Boston Globe, where he had previously worked as a roving reporter, and pitched the idea of “publishing daily updates from the glacier and they immediately got it!” With their track record of producing award-winning live coverage, that’s no surprise.

The recovery mission

He had the platform and the publisher. Now to to tell the story. And what a story it was. “It had all the elements… it was an opportunity to tell a story with real drama about a place people knew nothing about.” In a bid to fulfill its promise to leave no man behind, the U.S. coastguard and military, with Mitchell’s help, were attempting to excavate three bodies that been frozen into the glaciated landscape for over 60 years. They knew the approximate location of the fallen soldiers but, up against the elements in one of the most remote corners of the globe, nothing was certain. “Days were very, very intense … certain days the weather was bad and work was awful.” But this exhaustion was balanced with exhilaration; the exhilaration of being somewhere “so magnificent, so spectacularly beautiful,” he recalls.

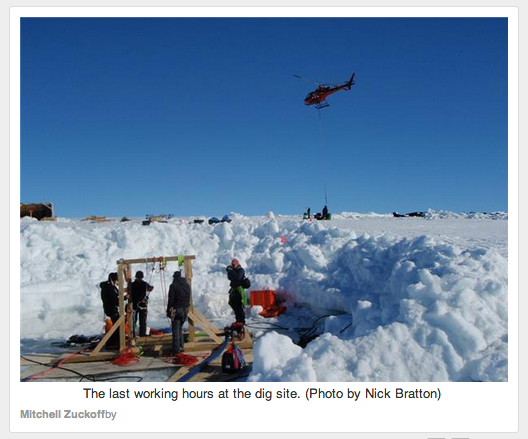

So, what does the day-to-day of a recovery mission in Koge Bay involve? Quite a lot of digging, a fair bit of shoveling and a bit of drilling, spiced up with sub-zero temperatures, ferocious winds and temperamental machines. “I was sore in muscles I didn’t know I had.” This post about sums up their daily tasks:

Our schedule for the day was set. We’d swarm from base camp to the dig site in teams, wave after wave of orange-booted, heavy-gloved, shovel-ready workers, primed to spend two-and-a-half-hour shifts from morning until night, expanding the snow-free zone above the target area.Then we woke up. A night of frigid wind that rattled our tents as it swept across the glacier had hardened the snow. We might as well have tried using shovels to move concrete.

But no matter what Mitchell was doing, whether it was digging a latrine or manning a machine, in the back of his mind he was formulating his daily post. He describes it like being back on deadline. “You’re always working, you had to feed the beast. It was my master.” Equipped with a special waterproof notebook – apparently everything is wet in the snow – Mitchell would jot down his ideas or quotes for the daily update, knee-deep in ice. Then, at the end of the day, he – or one of the guest writers – would put all his notes together as a post and update the Scribble event. Mitchell enlivened the text with tales of camaraderie, hijinks and lessons in greenlandic culture, while slideshows and video clips of the haunting landscape added the necessary colour. It just goes to show that real-time doesn’t have to be short, quick fire updates but can be nuanced long-form journalism.

An engaged readership

What sets this log apart from more conventional mediums is the proximity between the reporter and reader; his updates are published alongside his audience’s. Some comments are from people who have stumbled across the event, others are fans of his book, while lots are actually messages of support from family members for whom the live event is the best way to keep in touch with loved ones. “Hi Dad! Love you and miss you! I am so proud of the work you and the team are doing,” Mitchell’s daughter writes. In another, the mother of an expedition member writes to her son about the “record breaking temperatures” at home, rubbing salt into frozen wounds somewhat. It was the perfect way for family members to know that their loved ones were safe. “I met [project manager] Joe Tuttle’s wife,” Mitchell explains, “and she said it was so wonderful because she knew exactly what Joe was up to: ‘I knew he was safe; I was there with you.'”

Making a reader feel as if they are there with you, living and breathing the action; as a reporter you can’t ask for much more than that. But that wasn’t the case just for family members. “Mitchell, love your blog! Thanks for the opportunity to follow this amazing adventure,” wrote one reader but it just about sums up the response from the audience at large.

Their comments are supportive, encouraging and full of gratitude and were apparently hugely important to the team. “It was great because [we knew] people cared about what we were doing, that somebody out there was at home reading and caring about it,” recalls Mitchell. This sort of interaction was at the opposite end of the publishing spectrum to what he had experienced before, as he was getting instant feedback on his work. “I’ve been writing books. You go under a rock for a couple of years, then there’s six months for the publishing process and then you get the feedback,” he explained. But with the Scribble event, people are responding in real-time. “That was wonderful – so great, so reinforcing.” And the readers kept coming back, rapt by the story, the journey and the struggles of the expedition members.

‘The work is finished’

But Mitchell at least has been bewitched by Greenland and the glaciers, “the sound of silence” lingering on. If, for whatever reason, the memories of the frozen landscape start to escape him, they’ll always have this archive, this augmented journal that charts their experiences. “That’s the exciting thing for me,” admits Mitchell.

Frozen in Time tells the story of a group of people who went to Greenland to recover the bodies of their countrymen who, sixty years earlier, made the ultimate sacrifice and Mitchell’s desire to try out new forms of storytelling made it accessible to anybody who was interested. So next time stuttering wifi is getting on your nerves, think of Mitchell, perched on a rock in the bitter cold, searching for signal with his BGAN pointed at the sky.