First episode is here.

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Joseph Campbell, a literature professor at Sarah Lawrence College, unpacks his theory that all mythological narratives share the same basic structure.

He refers to this structure as the “monomyth” (all hero myths share the same frame or structure) or Hero’s Journey. Campbell summarises saying:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered, and a decisive victory is won: the Hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Joseph Campbell

The Hero’s Journey is a common narrative archetype, or story template, that involves a hero who goes on an adventure, learns a lesson, wins a victory with that newfound knowledge, and then returns home transformed.

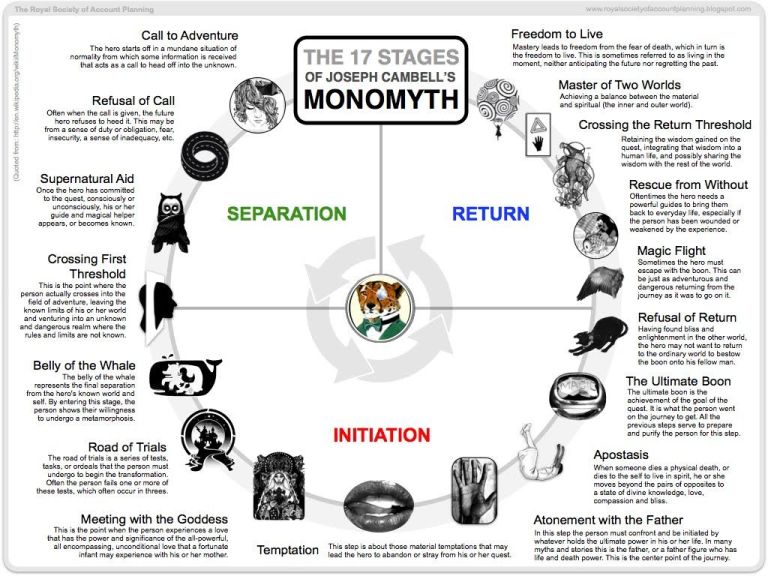

Campbell lays out 17 total stages of the Hero’s Journey structure. However, not all monomyths necessarily feature all stages or in the same order that Campbell described.

His theory is masculine-centric, which is why we will talk about Hero and not Heroin.

His theory had a huge influence, but at the same time, he had a very narrow view of gender, including the role of women.

The Journey includes Freudian elements too, like the confrontation with the father.

Campbell’s Hero Journey Model

The Hero’s journey can be boiled down to three essential stages:

- The departure: The Hero leaves the familiar world behind.

- The initiation: The Hero learns to navigate the unfamiliar world.

- The return: The Hero returns to the familiar world.

Let’s explore the details of the three stages:

Departure

In brief, the Hero is living in the so-called “ordinary world” when he receives a call to adventure.

Usually, the Hero is unsure of following this call — this phase is known as the “refusal of the call” — but is then helped by a mentor figure, who gives him counsel and convinces him to follow the call.

Initiation

In the initiation section, the hero enters the “special world,” where he begins facing a series of tasks until he reaches the story’s climax — the main obstacle or enemy.

Here, the hero puts into practice everything he has learned on his journey to overcome the obstacle.

Campbell talks about the hero attaining some kind of prize for his troubles — this can be a physical token or “elixir”, or just good, old-fashioned wisdom (or both).

Return

Feeling like he is ready to go back to his world, the hero must now leave.

Once back in the ordinary world, he undergoes a personal metamorphosis to realize how his adventure has changed him as a person.

The Hero Journey includes some psychological models borrowed from Jung and Freud. In fact, Campbell thought the hero teaches something about ourselves.

Here are all 17 steps of the Hero’s journey, as outlined by Campbell:

The departure:

1. The call to adventure: Something, or someone, interrupts the hero’s familiar life to present a problem, threat, or opportunity.

2. Refusal of the call: Unwilling to step out of their comfort zone or face their fear, the hero initially hesitates to embark on this journey.

3. Supernatural aid: A mentor figure gives the hero the tools and inspiration they need to accept the call to adventure.

4. Crossing the threshold: The hero embarks on their quest.

5. Belly of the whale: The hero crosses the point of no return and encounters their first major obstacle.

The initiation:

6. The road of trials: The hero must go through a series of tests or ordeals to begin his transformation. Often, he fails at least one of these tests.

7. The meeting with the goddess: The hero meets one or more allies, who pick him up and help him continue his journey.

8. Woman as temptress: The hero is tempted to abandon or stray from his quest. Traditionally, this temptation is a love interest, but it can manifest itself in other forms as well, including fame or wealth.

9. Atonement with the father: The hero confronts the reason for his journey, facing his doubts and fears and the powers that rule his life. This is a major turning point in the story: every prior step has brought the hero here, and every step forward stems from this moment.

10. Apotheosis: As a result of this confrontation, the hero gains a profound understanding of their purpose or skill. Armed with this new ability, he prepares for the most difficult part of the adventure.

11. The ultimate boon: The hero achieves the goal he set out to accomplish, fulfilling the call that inspired his journey in the first place.

The return:

12. Refusal of the return: If the Hero’s journey has been victorious, he may be reluctant to return to the ordinary world of his prior life.

13. The magic flight: The hero must escape with the object of his quest, evading those who would reclaim it.

14. Rescue from without: Mirroring the goddess’s meeting, the hero receives help from a guide or rescuer to make it home.

15. The crossing of the return threshold: The hero makes a successful return to the ordinary world.

16. Master of two worlds: We see the hero achieve a balance between who he was before his journey and who he is now. Often, this means balancing the material world with the spiritual enlightenment he’s gained.

17. Freedom to live: We leave the hero at peace with his life.

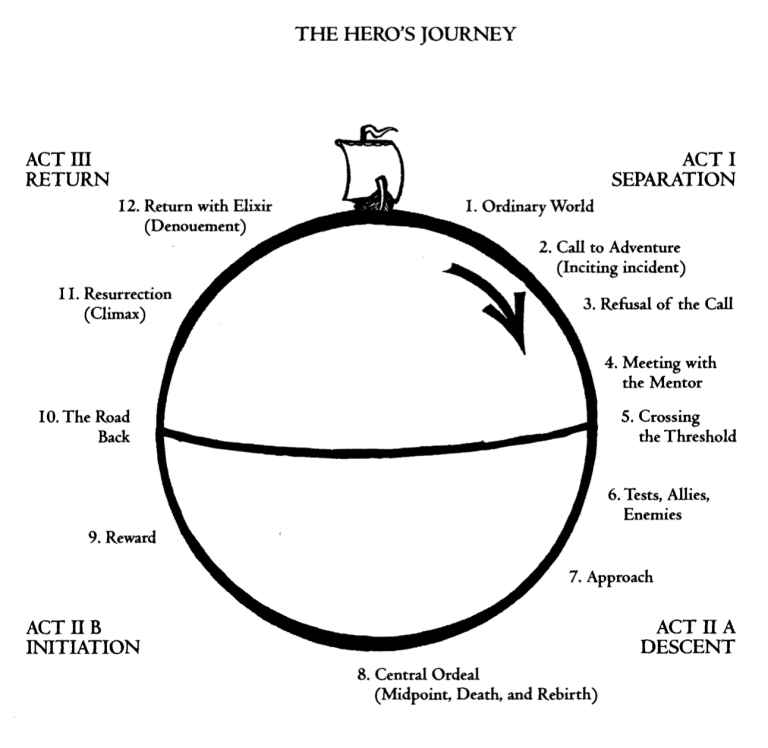

Vogler’s Hero Journey model

Christopher Vogler, Hollywood film producer and writer, was influenced by Joseph Campbell’s Hero Journey.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces has influenced writers across literature, music, films, and video games.

Perhaps most famously, George Lucas credited Campbell for influencing the structure of the Star Wars films.

In the late ’90s, Christopher Vogler, a Hollywood film producer and writer, created a seven-page memo titled “A Practical Guide to The Hero With a Thousand Faces”, intended to help Hollywood writers wrap their heads around Campbell’s monomyth structure.

The memo was later developed into a screenwriting textbook, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers (1992).

The 12 stages of the HERO are:

1. The Hero is introduced in his ordinary world

Most stories take place in a special world, a world that is new and alien to its hero.

In Witness, you see both the Amish boy and the policeman in their ordinary worlds before they are thrust into alien worlds — the farmboy into the city and the city cop into the unfamiliar countryside.

In Star Wars, you see Luke Skywalker bored to death as a farm boy before he takes on the universe.

2. The call to adventure

The hero is presented with a problem, challenge, or adventure. In Star Wars again, Princess Leia’s holographic message to Obi Wan Kenobi asks Luke to join in the quest.

In detective stories, it’s the hero accepting a new case. In romantic comedies, it could be the first sight of that special — but annoying — someone the hero or heroine will be pursuing/sparring with the remainder of the story.

3. The Hero is reluctant at first

Often at this point, the hero balks at the threshold of adventure. After all, he or she is facing the greatest of all fears: the fear of the unknown.

At this point, Luke refuses Obi Wan’s call to adventure and returns to his aunt and uncle’s farmhouse, only to find the Emperor’s stormtroopers have killed them.

Suddenly Luke is no longer reluctant and is eager to undertake the adventure. He is motivated.

4. The Hero is encouraged by the wise old man or woman

By this time, many stories will have introduced a Merlin-like character who is the hero’s mentor.

In Jaws, it’s the crusty Robert Shaw character who knows all about sharks. The mentor gives advice and sometimes magical weapons. This is Obi Wan Kenobi giving Luke Skywalker his father’s light sabre. The mentor can only go so far with the hero.

Eventually, the hero must face the unknown by himself. Sometimes the wise old man is required to give the hero a swift kick in the pants to get the adventure going.

5. The Hero passes the first threshold

He fully enters the special world of his story for the first time. This is the moment at which the story takes off, and the adventure gets going.

The hero is now committed to his journey, and there’s no turning back.

6. The Hero encounters allies, tests and helpers

The Hero is forced to make allies and enemies in the special world and pass certain tests and challenges that are part of his training.

In Star Wars, the cantina is the setting for the forging of an important alliance with Han Solo, and the start of an important enmity with Jabba The Hut.

In many western movies, it’s the saloon where these relationships are established. The tests and challenges phase is represented in Star Wars by Obi Wan’s scene teaching Luke about the Force, as Luke is made to learn by fighting blindfolded.

The early laser battles with the Imperial Fighters are another test which Luke passes successfully.

7. The Hero reaches the inmost cave

The hero comes at last to a dangerous place, often deep underground, where his quest’s object is hidden.

In the Arthurian stories, the Chapel Perilous is the dangerous chamber where the seeker finds the Grail.

In many myths, the hero has to descend into hell to retrieve a loved one or into a cave to fight a dragon and gain a treasure.

In Star Wars, it’s Luke and company being sucked into the Death Star, where they will rescue Princess Leia.

Sometimes it’s the hero entering the headquarters of his nemesis, and, sometimes, it’s just the hero going into his or her own dream world to confront his or her worst fears and overcome them.

This is the moment at which the hero touches the bottom. He faces the possibility of death, brought to the brink in a fight with a mythical beast.

8. The Hero endures the supreme ordeal

For us, the audience standing outside the cave waiting for the victor to emerge, it’s a black moment.

In Star Wars, it’s the harrowing moment in the bowels of the Death Star, where Luke, Leia and company are trapped in the giant trash-masher.

Luke is pulled under by the tentacled monster that lives in the sewage and is held down so long the audience begins to wonder if he’s dead.

This is a critical moment in any story, an ordeal in which the hero appears to die and is born again. It’s a major source of the magic of the hero myth.

What happens is that the audience has been led to identify with the hero. We are encouraged to experience the brink-of-death feeling with him.

We are temporarily depressed, and then we are revived by the hero’s return from death.

9. The Hero seizes and grabs the sword

Having survived death, beaten the dragon, the hero now takes possession of the treasure he’s come seeking.

Sometimes it’s a special weapon like a magic sword, or it may be a token like the Grail or some elixir that can heal the wounded land.

Sometimes the “sword” is knowledge and experience that leads to greater understanding and reconciliation with hostile forces.

The hero may settle a conflict with his father or with his shadowy nemesis.

In Return of the Jedi, Luke is reconciled with both, as he discovers that the dying Darth Vader is his father. The hero may also be reconciled with a woman.

Often she is the treasure he’s come to win or rescue, and there is often a love scene or sacred marriage at this point.

The hero’s supreme ordeal may grant him a better understanding of women, leading to a reconciliation with the opposite sex.

10. The road back

The hero’s not out of the woods yet. Some of the best chase scenes come at this point, as the hero is pursued by the vengeful forces from whom he has stolen the elixir or the treasure.

This is the chase as Luke and friends escape from the Death Star, with Princess Leia and the plans that will bring down Darth Vader.

If the hero has not yet managed to reconcile with his father or the gods, they may come raging after him at this point.

11. Resurrection

The hero emerges from the special world, transformed by his experience.

There is often a replay here of the mock death-and-rebirth of stage 8, as the hero once again faces death and survives.

Each ordeal wins him new command over the Force. He is transformed into a new being by his experience.

12. Return with the elixir

The hero comes back to his ordinary world, but his adventure would be meaningless unless he brought back the elixir, treasure, or some lesson from the special world.

Sometimes it’s just knowledge or experience, but unless he comes back with the elixir or some boon to mankind, he’s doomed to repeat the adventure until he does.

Sometimes the benefit is treasure won on the quest, or love, or just the knowledge that the special world exists and can be survived. Sometimes it’s just coming home with a good story to tell.

Many authors have used monomyth in literature and popular fiction. Look at the two examples below.

The Matrix (1999)

The ordinary world: Thomas Anderson is a bored computer programmer by day and the hacker “Neo” by night.

The call to adventure: Neo receives a message promising him that everything is not as it seems. He is told to “follow the white rabbit”.

Refusal of the call: Neo isn’t sure if Trinity is telling him the truth. He allows himself to be captured.

Mentor: Morpheus gives Neo a choice: the blue pill if he wants to return to his old life or the red pill if he wants to know the truth.

Crossing the threshold: Neo chooses the red pill and is shown what the Matrix is.

The ordeal: Neo struggles to accept his new role but ultimately learns to become who he was meant to be, defeating Agent Smith inside the Matrix and saving Morpheus.

The return: Neo tells the machines he will defeat them and save humanity.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (1954)

The ordinary world: Frodo lives in the Shire, enjoying a nice, peaceful life with his friends.

The call to adventure: Following Gandalf’s discovery of the ring of power, he asks Frodo to undertake a journey and keep the ring with him.

Refusal of the call: Frodo is unsure of leaving the Shire, as he has no experience with the world outside.

The mentor: Gandalf convinces Frodo that he has a pure heart, and he is the one who must “bear this burden”.

Crossing the threshold: Frodo and Sam leave the Shire behind, a moment that Frodo has mixed feelings about.

The ordeal: Characterized by the many challenges Frodo faces along the way with the Fellowship, including the fight with the Balrog.

The return: Frodo realizes that he can no longer be part of the Fellowship and must continue on the journey alone. He sets out for Mount Doom.

End of Episode 2.

Next Episode: Strategic Storytelling: Where Business And Stories Meet

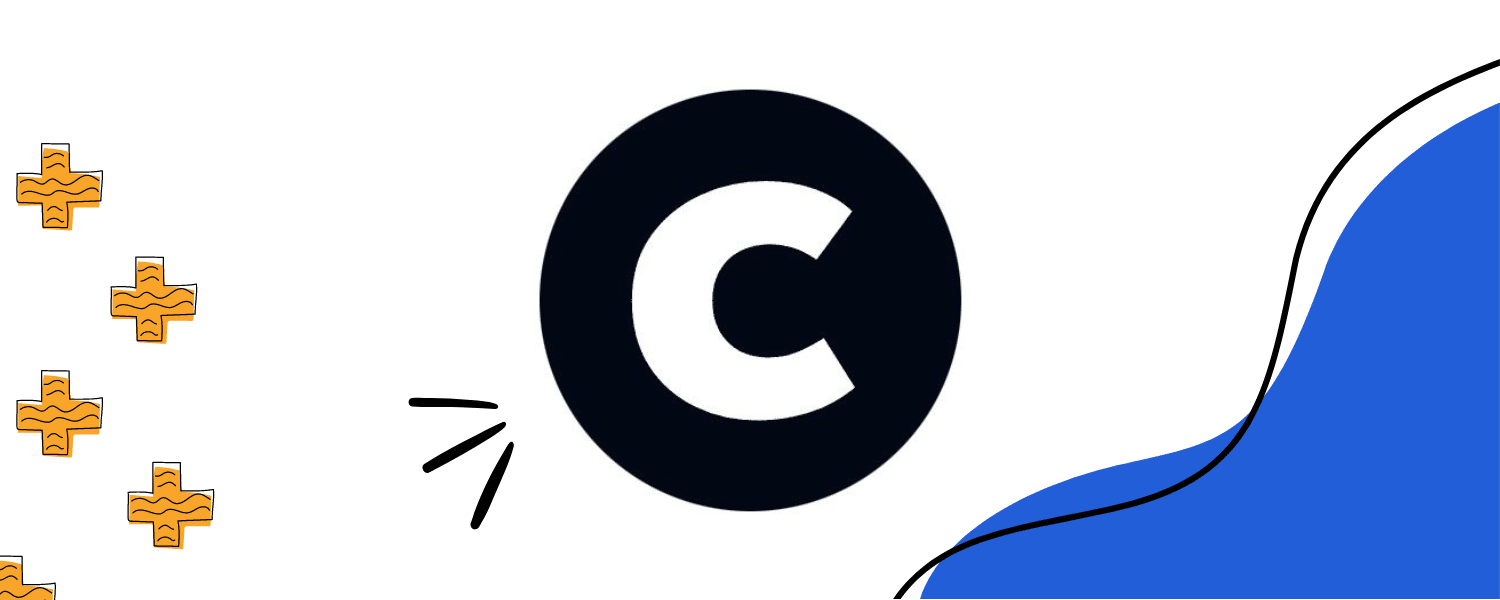

As you delve into the rich tapestry of storytelling, consider expanding your narrative horizons with WriterAccess.

Our platform hosts a community of adept freelancers, honing their skills in the delicate craft of strategic storytelling. Picture having seasoned writers who grasp the essence of the hero’s journey and contemporary storytelling techniques, seamlessly weaving narratives that resonate.

It’s more than just a platform; it’s your gateway to unlocking the full potential of your business narrative. Ready to embark on this storytelling adventure? Join us at WriterAccess and experience the art of narrative evolution.